Oxytocin, Resilience, and the Politics of Human Enhancement

Guest: Professor Julian Reid, University of Lapland, Finland

Presented by: Azher Hameed Qamar

Introduction

In this thought-provoking and interdisciplinary lecture, Professor Julian Reid, a leading scholar in international politics, political theory, and biopolitics, explores a compelling intersection of neuroscience and political science. With clarity and depth, he invites us to examine how discoveries in neurobiology—specifically the role of the hormone oxytocin—are increasingly influencing concepts of resilience, governance, and the organization of human life in the twenty-first century.

The discussion forms part of a broader scholarly project on Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) and social resilience. However, this lecture zooms in on how emerging biomedical and neurochemical understandings of human behavior are being mobilized in political and social policy spaces, particularly in the realms of security, militarization, and psychological well-being. Professor Reid introduces a critical lens to help us ask: What does it mean to biologize resilience? Can a hormone like oxytocin become a political tool? What are the ethical and philosophical consequences of these developments?

Biopolitics, War, and the Evolution of Resilience

Professor Reid begins by reflecting on his earlier work on the biopolitics of war, a field of inquiry that explores how liberal democracies engage with life—not only to protect it but also to regulate, manage, and optimize it. His prior work includes the questions such as how states exert control over populations by intervening in their biological and psychological capacities.

Over time, Reid shifted his focus to the concept of resilience. In liberal governance, resilience has become a buzzword—used across disaster management, public health, education, climate change, and international relations. But rather than simply celebrating resilience as a virtue, Reid critiques its instrumentalization. In his view, resilience is now framed not as a collective good but as an individual obligation: the ability to adapt, survive, and thrive amid adversity without demanding structural change.

Resilience discourse, especially in neoliberal governance, often justify the state of responsibility while placing the burden on individuals and communities to cope with trauma, disruption, or inequality. This framing fits neatly into broader shifts in governmentality where people are encouraged to become “entrepreneurs of themselves,” responsible for their own survival and well-being.

The Neuroscience of Oxytocin

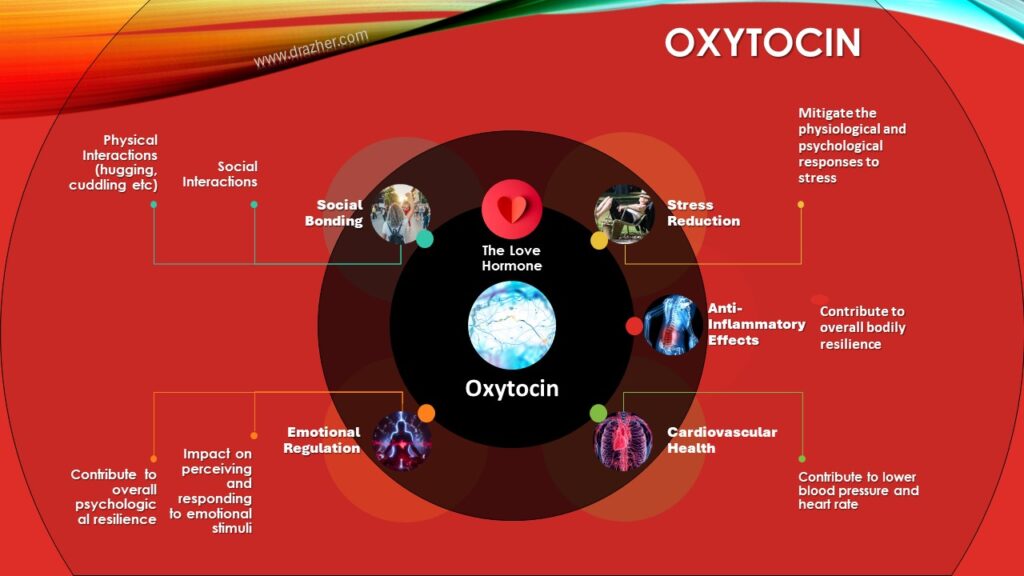

Discussing oxytocin, Reid introduces us to this small but powerful hormone, often referred to as the “love hormone” or “bonding hormone.” Oxytocin is a neuropeptide involved in a range of physiological processes, from childbirth and breastfeeding to empathy, trust, and prosocial behavior.

Importantly, oxytocin has a long evolutionary history, appearing in animals as diverse as rats, sheep, and humans. Its role in facilitating bonding between mother and child, as well as among social groups, has made it a central focus of recent neuroscientific studies on resilience and emotional health.

Oxytocin is the biological basis for many of our most valued social experiences: love, empathy, connection, and even moral behavior. Research suggests that people who have higher levels of oxytocin or more sensitive oxytocin receptors are better able to form secure attachments and recover from psychological stress.

This emerging science has sparked intense interest among policymakers, military strategists, and public health experts. If oxytocin can foster trust, promote empathy, and reduce fear, might it be harnessed to enhance social cohesion, reduce xenophobia, or even prevent conflict?

Resilience as Biological Enhancement

Reid cautions against the uncritical embrace of these findings. While the neurobiological research on oxytocin is undoubtedly fascinating, its integration into political and military agendas raises profound ethical questions. He explains how, since the 2014 Crimea crisis, NATO has begun to rethink its strategic frameworks—placing emphasis on psychological resilience as a critical aspect of national defense.

Rather than focusing solely on material infrastructure or military might, NATO and its partners are increasingly interested in “psychological resilience” of populations. In this framework, a resilient citizen is not merely one who resists invasion but someone who remains calm, trusting, and cooperative even in the face of adversity.

Here, oxytocin becomes not just a hormone but a tool of governance. It is imagined as a neurochemical intervention to create socially stable, emotionally balanced, and politically compliant subjects. Military experiments with oxytocin are not just theoretical: in studies involving rats and humans, oxytocin has been shown to reduce fear responses and increase group loyalty. But these effects are double-edged. The same hormone that promotes bonding can also heighten in-group bias and aggression toward outsiders.

Reid invites us to consider the implications: If states or militaries begin to use biochemical means to influence public emotion or perception, what happens to agency, freedom, and the pluralism of democratic life?

Storytelling, Ritual, and the Social Construction of Meaning

Reid emphasizes that oxytocin does not act in isolation. Its release is often triggered by narratives, rituals, and shared cultural practices. This insight opens another layer of inquiry: how do stories—religious, political, or national—influence our biology?

He refers to work showing how group rituals (such as singing, praying, or dancing) elevate oxytocin levels and generate feelings of trust and unity. This has important implications for understanding how ideologies function at the emotional and neurochemical level. Nationalism, religious solidarity, and collective memory may all have hormonal components.

Reid suggests that organizations such as DARPA (the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) are exploring how stories and rituals might be strategically used to enhance resilience or foster allegiance. Could we be moving toward a world in which narratives are not only socially but biologically engineered?

Toward a Critical Neuro-social Science

In the final part of the lecture, Reid argues for a new interdisciplinary dialogue. Neuroscience must be enriched by insights from anthropology, sociology, philosophy, and political science. While neurobiological research offers valuable tools, it cannot explain human behavior in its full complexity.

Equally, social scientists must resist dismissing biological approaches. Instead, they should engage critically with these findings, asking how biology interacts with culture, power, and politics. The goal is not to refute science but to contextualize it ethically and socially.

Reid warns against what he calls “neuro-optimism”—the belief that biological solutions can solve deeply historical, structural, or moral problems. The risk is that issues such as racism, inequality, and war will be framed as hormonal imbalances rather than as outcomes of unjust systems.

Conclusion: Ethics, Empathy, and Responsibility

This lecture challenges us to think beyond disciplinary boundaries. It asks us to recognize the interconnectedness of mind, body, and society. It also highlights the need for critical engagement with emerging biotechnologies and neuroscientific trends.

As Professor Reid reminds us, resilience is not just a capacity but a concept shaped by politics, power, and ethics. Oxytocin may help us bond, but it is our collective responsibility to decide what kind of bonds we want to build.

We are left with essential questions: How can we foster resilience without manipulation? How can we integrate science and ethics? And ultimately, how do we protect human dignity in an age of neurochemical governance?

For further reading, see Professor Julian Reid’s work on resilience, liberal governance, and the biopolitics of war.