Rethinking Climate Adaptation: A Social Lens on Resilience

Climate change research has paid little attention to the social dimensions of resilience and their link to social capital. The article “Social dimensions of resilience and climate change: a rapid review of theoretical approaches” reviews 27 studies (18 directly relevant) to explore how social capital connects with resilience.

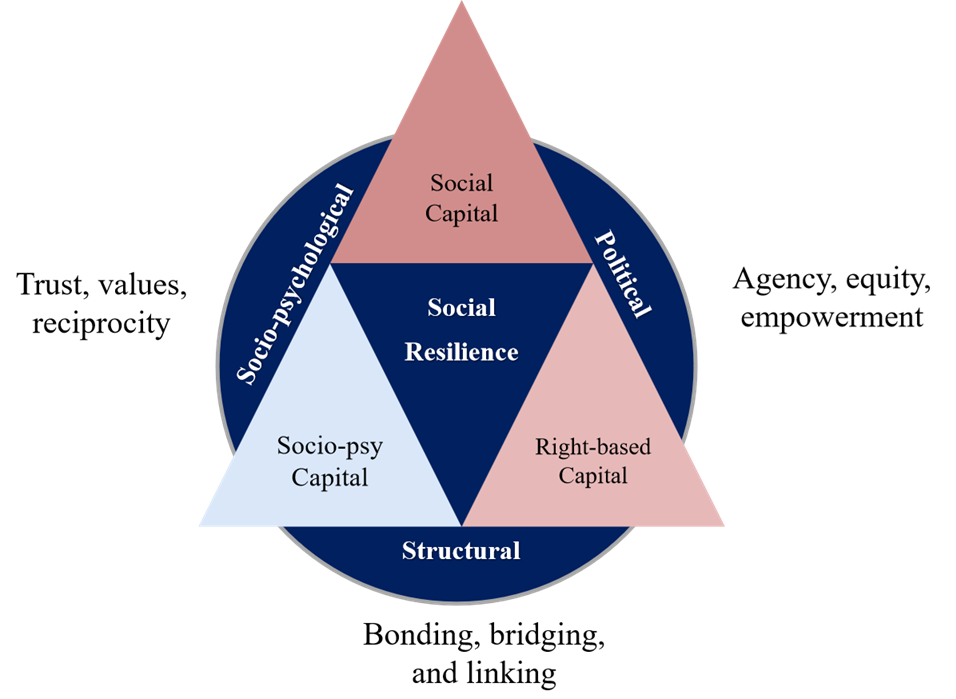

Findings show three key approaches:

- Structural – bonding, bridging, and linking networks form the foundation of social capital.

- Social-psychological – cognitive social capital (trust, values, reciprocity) supports collective psycho-social resilience.

- Human rights-based – highlights equity and power in shaping resilience.

Together, these dimensions show that communal solidarity and interconnectedness—through networks, values, and inclusive action—are essential for resilience to environmental threats. The article argues for theoretical triangulation to integrate these perspectives in climate change studies.

This post summarizes the following article:

Qamar, A. H. (2023). Social dimensions of resilience and climate change: a rapid review of theoretical approaches. Present Environment and Sustainable Development, 17(1), 139-153.

Rising global temperatures signal extreme events and climate-related disasters, which affect communities through food insecurity, migration, and disrupted livelihoods. Agricultural and coastal populations are especially vulnerable.

Research highlights the role of social capital—both structural (networks, systems) and cognitive (trust, values, reciprocity)—in building resilience. These dimensions support collective action, resource-sharing, and recovery during crises. Yet, the social aspects of resilience remain underexplored in climate change studies, which often overlook how social capital actually shapes resilience processes.

This article reviews studies linking climate change, social capital, and resilience. It emphasizes that resilience is not only psychological but also social, requiring attention to vulnerability, human rights, and socio-ecological interdependence. Social organization and networks are vital for communities to adapt, withstand, and recover from crises.

The review identifies a gap: while the role of social capital in disaster recovery is documented, its contribution to social resilience in climate change is rarely studied. The article calls for theoretical triangulation—integrating multiple approaches to better understand how social capital, resilience, and climate interact in shaping adaptive strategies.

Method

This review examines:

- Theoretical approaches to social capital in climate change, and

- The social dimensions of resilience that link social resilience and social capital.

Using the Scopus database, the search focused on English-language journal articles (2000–2022) in the social sciences, psychology, humanities, and economics. Titles had to include the words Social, Resilience, and Climate.

From 27 results, 18 articles were selected for detailed review. These were analyzed to identify and describe the theoretical approaches used to study the social dimensions of resilience in climate change.

Theoretical Approaches – Review Findings

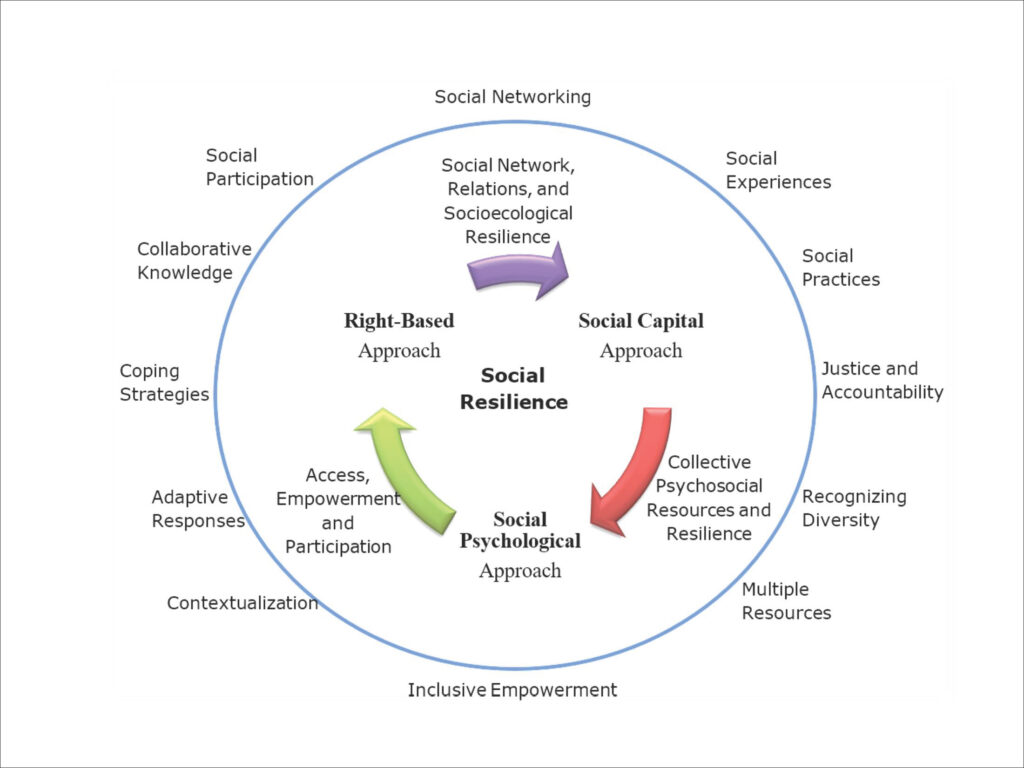

This review identified a wide range of resilience-building strategies for climate change, disasters, food insecurity, and livelihood threats. These include: diversifying income and productive activities, reducing expenses, strengthening social participation and networks, promoting collaborative learning, supporting self-organization, ensuring justice and equity, enhancing governance, and integrating local with scientific knowledge.

All strategies are closely tied to different forms of social capital—economic, social, cultural, and political. Inclusive participation and diversity are emphasized as strengths, helping communities build productive networks and collective resilience.

Overall, resilience depends on connecting people and institutions, combining psychological and social resources, and designing context-specific interventions. Three main approaches frame this understanding: the social capital approach, the social psychological approach, and the rights-based approach.

Social Capital Approach

The concept of social capital is widely used but not always clearly defined. Two major theorists shaped its meaning:

- Coleman emphasized bonding—internal ties within groups, built on trust and reciprocity, serving collective needs.

- Bourdieu highlighted bridging—external networks that provide access to resources and reveal social inequalities, linking social capital to broader power structures.

Research shows a positive relationship between social capital and resilience, with three key dimensions:

- Bonding – Close ties within families, friends, and communities that strengthen belonging. Strong trust, belonging, and identity – Emotional support and immediate help in crises

- Bridging – Connections across groups (e.g., race, religion, class) that create wider support networks. Wider networks and access to new resources – Collaboration and reduces isolation

- Linking – Vertical ties to institutions and the state, providing access to power and formal support. Relationships with organizations, institutions, and the state – Formal support, resources, and power – Connects communities to governance, policy, and structural change

Together, bonding, bridging, and linking form the structural foundation of social capital, each contributing to resilience by reinforcing identity, building networks, and connecting communities to resources and institutions.

Social Psychological Approach

Psychological capital focuses on individual traits like hope, self-efficacy, resilience, and optimism. The social psychological approach connects this to cognitive social capital—social identity, reciprocity, altruism, responsibility, and shared knowledge of risks—which together build collective psycho-social resources.

Shared trust, solidarity, and common narratives strengthen group resilience. Social psychology emphasizes group behavior as a bottom-up path to resilience, where tighter social norms and collective practices (e.g., shared labor, risk, and resources in farming or fishing) act as internal supports.

Adversity links social, economic, and physical insecurities, but awareness of shared challenges fosters belonging and collective action. Through common context and language, communities build shared resilience, supported by the cognitive dimension of social capital—mutual trust, commitment, and confidence that reinforce psycho-social strength.

Human Right-Based Approach

The human rights-based approach to resilience focuses on equity, power, and inequality. It emphasizes that human rights apply to all people regardless of status, and resilience must be understood in relation to social, cultural, and political power structures that shape access to resources and decision-making.

This perspective links resilience practices to two key goals:

- Challenging narratives that normalize inequality and marginalization.

- Transforming systems toward more equitable political and social arrangements.

Resilience requires equal participation, empowerment, transparency, and accountability in decision-making. Equality must go beyond legal definitions to address structural marginalization and ensure marginalized groups have a voice.

Ultimately, the rights-based approach connects recognition of discrimination with the transformation of socio-political systems, aiming for social sustainability, justice, and well-being.

Theoretical Triangulation

A sustainable livelihood depends on the ability to withstand stress, recover, and build future capacities. Livelihoods are made up of people’s capabilities, assets, and activities. Adger defines social resilience as the capacity of individuals or communities to endure shocks and stresses without major disruption, where shocks are significant changes in social structures or livelihoods.

In the context of climate change, resilience links livelihood strategies, access to resources, and adaptive capacities. Studies highlight three forms of resilience: reactive (coping), responsive (adjustment and recovery), and proactive (anticipation and planning).

Ungar’s socio-ecological approach views resilience as shaped by person–environment interaction, cultural context, and individual capacities. Both psychological resources (internal traits) and social resources (family, networks, institutions) support resilience. Overemphasizing individual traits risks ignoring the role of institutions, structures, and practices.

In disaster contexts, resilience also refers to the ability of social structures and relationships to absorb shocks and adapt to prevent future crises. While widely cited, research on social resilience in climate change remains limited, though Adger’s work continues to emphasize its importance for sustainable development.

In this context on community resilience, Social resilience helps explain the social dimensions of resilience and social capital. It is shaped by livelihoods, access to resources, and social institutions, enabling individuals, groups, or systems to absorb, adapt, recover, and reorganize in the face of shocks such as policy changes, conflict, or environmental hazards.

The concept “Social Resilience” is especially useful for studying climate change impacts, the role of community social capital, and strategies for coping and recovery. By focusing on the “how” of resilience, researchers can better contextualize community responses within the social dynamics of climate change.

This review highlights three interconnected approaches to framing social capital and resilience in the context of climate change:

- Social capital approach – focuses on networks from in-groups to wider institutions, providing structural resources.

- Social-psychological approach – emphasizes shared risk, identity, and belonging, explaining collective solidarity and resilience.

- Rights-based approach – addresses inequalities and power relations, aiming for transformation through participation, empowerment, and equity.

Together, these approaches form a triangular perspective of resilience, showing how psychological, social, and political resources interact. The review proposes theoretical triangulation—integrating all three—to build a more holistic understanding of resilience and social sustainability.

Key conclusions:

- Social resilience is a social process linking different dimensions of social capital.

- It is anchored in environmental change and societal impacts.

- Interdisciplinary and participatory approaches are needed to study resilience, emphasizing agency, empowerment, and collaborative knowledge.

This framework provides a conceptual roadmap for future research, encouraging bottom-up, qualitative studies that capture the diversity of community responses to climate change.

Read full article.

Qamar, A. H. (2023). Social dimensions of resilience and climate change: a rapid review of theoretical approaches. Present Environment and Sustainable Development, 17(1), 139-153.