“Every Time You Say, ‘Oh, They’re So Resilient,’ That Means You Can Do Something Else to Me.”

What does it really mean to call someone “resilient”? And who benefits from it?

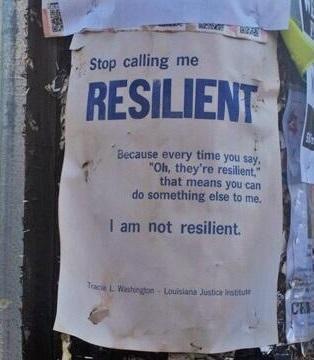

People often use the word “resilient” as a compliment for those who’ve been through really tough times. It sounds like praise — like saying someone is strong for surviving hardship. But there’s a quote in the poster “Stop calling me RESILIENT” by Tracie Washington that she presented in the street of New Orleans in 2005. It points out something important: “Every time you say, ‘Oh, they’re so resilient,’ that means you can do something else to me.”

This quote makes us think twice. It shows how calling someone resilient can sometimes be a way to avoid helping them. Instead of offering support, people might just expect others to keep pushing through — even in unfair or painful situations. So while resilience sounds like a good thing, its popular conceptualization as ability or capacity or personal characteristics to withstand and bounce-back draws a line between resilient and non-resilient. This conceptualization may be used to excuse neglect or ignore deeper problems.

The Dominant Paradigm: Resilience as Psychological Fitness

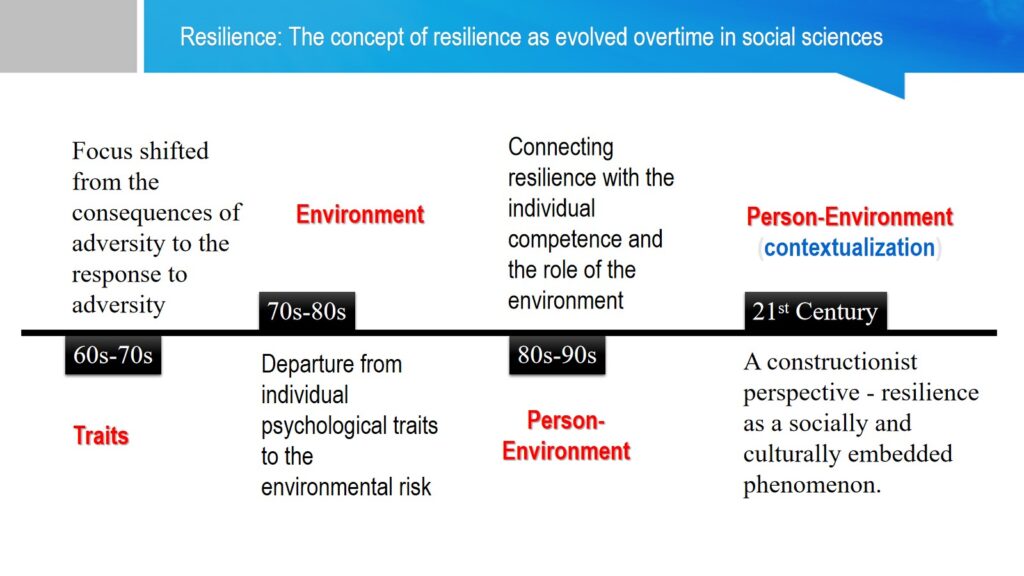

By the late 1900s, people started thinking of “resilience” as something personal — like a kind of mental strength that helps someone get through hard times. Researchers back then focused on things inside a person, like confidence, personality, or how smart they were. These were seen as the ingredients for being resilient.

But this way of thinking created a divide: either you had these qualities and were called “resilient,” or you didn’t — and were seen as weak or lacking something. That can lead to unfair judgments, where people struggling aren’t seen as needing support, but instead blamed for not being “strong enough.”

Critics like Estêvão et al. (2017) have called this framing “heroic resilience” — a narrative that celebrates personal grit while ignoring the institutional constraints and unequal access to resources. As they note, this version of resilience “seems to ignore the relationship between institutions and individuals or social structures and social practices”.

The Neoliberal Spin: Survive or Be Left Behind

This individualist framing aligns neatly with neoliberal ideologies. If resilience is merely about personal strength, then those who fail to thrive can be blamed — and abandoned. Neoliberalism reduces social problems to personal failures and promotes a logic of “best fit” or “survival of the most resilient,” while dismantling collective safety nets (Alietti, 2021).

In this case, “resilience” stops being a compliment and turns into an expectation: either you adapt to tough situations, or you get left behind. It puts pressure on individuals to keep going no matter what, while ignoring the bigger, unfair systems that make life so hard in the first place.

Instead of fixing those deeper problems, society often pushes people to adjust and cope — and if they can’t, they’re seen as failures. It’s like saying, “It’s your job to survive this, no matter how unfair it is.”

The Limitations of Quantification

Despite growing interest in resilience across disciplines, many attempts to measure it remain rooted in quantitative models that generalize environmental variables without accounting for social, cultural, and political complexity. These models often ignore the lived experiences, meaning-making processes, and relational dynamics that constitute real-world resilience — especially in marginalized communities (Qamar 2024; Qamar 2023).

What’s missing is not just more data, but better questions.

Toward a New Understanding: Social Resilience as Dynamic and Relational

We must move beyond the binary of “resilient/non-resilient” and toward an understanding of resilience as a process — ongoing, collective, and embedded in the everyday lives of people and communities.

As Keck and Sakdapolrak (2013) argue, social resilience is not a static capacity but a dynamic, context-dependent process that unfolds through struggle, adaptation, and transformation. It involves the integration of coping, adaptive, and transformative capacities — not in isolation, but in continuous interaction with environments, institutions, and communities.

“Social resilience is a social phenomenon characterized by several interconnected social, cultural, economic, and political factors” (Qamar, 2023). This perspective emphasizes agency, not a personal trait, but as a relational and collective practice. Resilience becomes visible in how people create and rebuild networks, interact with institutions, and develop new meanings of survival, care, and community.

From Bouncing Back to Bouncing Ahead

In contexts like migration, social resilience is especially salient. Migrants often face disrupted lives, unstable legal status, and systemic exclusion. Yet, through their lived experiences, they engage in complex negotiations of belonging, visibility, and support. Their resilience is not heroic or individual — it is collective, situated, and political. Qamar (2023) frames this through four key aspects of social experience: status, network, support, and visibility — all of which are institutionally anchored and shaped by structural conditions. The concept of “bouncing ahead” to a “new normal” — not merely returning to the old one — highlights migrants’ transformational capacities in the face of dislocation.

The PECS Framework and the Practice of Resilience

Social resilience is deeply intertwined with Political, Economic, Cultural, and Social (PECS) environmental factors. These shape the very context in which resilience is constructed — who gets to access resources, who gets heard, and who gets left out.

Resilience isn’t a finish line you reach — it’s something people actively do. It shows up in everyday actions like:

- Building support systems and leaning on others

- Figuring out how to work with, or sometimes push back against, institutions and rules

- Adjusting to life’s constant changes

- Making sense of experiences, both alone and with others

- Strengthening community ties and reconnecting with cultural roots

So resilience is not something you either have or don’t, resilience is about the ways people respond, adapt, and support one another through life’s challenges. It is about going through and getting through while re-learning and transformation to survive and thrive together.

Why Binary Conceptualizations Fall Short

The notion of a universal measurement of resilience or a binary distinction between the resilient and the non-resilient is both conceptually weak and politically dangerous. It obscures the complex, layered ways in which people and groups experience crises — and how they respond in ways that do not always fit tidy models. Such framing fails to “capture the layers of meaning in its environmental context and the process of meaning-making that emerges from interactive human experiences.” Without this nuance, resilience discourse becomes complicit in reinforcing marginalization.

Reframing Resilience as Collective Care and Justice

To reclaim the idea of resilience, we need to reframe it as a collective and ethical practice — not a test of individual worth. Social resilience is best understood as a set of relationships and responses that people mobilize to survive and thrive — often against the odds, and often with others. It is about adaptation and resistance, transformation and care. It’s what people do when they are not given the tools — and yet still find ways to build something together.

Final Thoughts

Resilience shouldn’t be treated like a prize for surviving unfair treatment. Instead, it should make us ask: Why was resilience even necessary in the first place? If we really care about people being strong in hard times, then we need to care even more about fixing the systems that keep making life so hard.

True support means standing with the people who face injustice daily — not just admiring their strength but working together to change the root causes that made them have to be so strong at all.